Adam and Whit set the stage.

I am so grateful for these community leaders who have given their time today to share their wisdom, experiences, and opinions about Utah Lake. I am also grateful to all those reporting on these issues and all those following along at home or at work. The biggest thing I’ve learned from this experience is that the vast majority of our community and leaders are well intentioned and want a bright future for Utah Valley and the lake at its center.

Whit on the fundamental importance of free speech.

A vibrant, free society depends on the open exchange of ideas, transparency in government, reliable information, and freedom of speech. Public disagreements and hard questions are needed at every step of big decisions about our community. I’m hard pressed to think of a bigger decision than the future of Utah Lake. Depending on how you think of it, this is a 150 square mile decision or a 30,000-year decision looking back to the Pleistocene origins of this unique water body.

Isabella reading Mary’s words about the sacredness of the lake.

The importance of free and open debate in making decisions makes this lawsuit really troubling. I have family, friends, and a professional network that have supported me and my family through this trauma, but I can’t shake this one question. What if this lawsuit had targeted someone else? What if the developers picked a college student, a single parent, or a working-class family speaking out about issues in their neighborhood? Do we want to live in a society where only those who can afford to retain permanent legal counsel can fully participate in public debate? Will we tolerate legal actions that dodge the hard questions and instead seek to silence citizens who are trying to understand and speak out about what is going on?

Elisabeth reading George’s words about leadership and stewardship.

Andrew talking about the societal and economic risk of mega projects.

Now let’s get back to the lake. Utah Lake is big geographically, but it’s ecological and cultural importance aren’t just a matter of size. This desert lake is an island of water in the vast sea of land that is the Great Basin. Consequently, it is a keystone ecosystem in western North America—supporting tens of millions of birds, fish, and other species. The lake is generous and resilient. As Chief Executive Meyer of the Timpanogos Nation has taught us, this lake has sustained multiple civilizations around its dynamic shoreline for more than 20,000 years. When my ancestors arrived less than 200 years ago, the bounty of the lake’s fishery saved them when their crops failed. Many of us literally would not be here if it weren’t for Utah Lake.

Carol-Lyn showing the packet that was delivered to every representative and senator today.

Since the arrival of the Pioneers, we have a mixed record with our stewardship of the lake. We introduced exotic fish to replace the native ones we overharvested. We changed the lake’s hydrology to meet our immediate needs, not anticipating the feedbacks and impacts that would have on the whole valley. Our excessive water diversions resulted in the lake drying up during the Dustbowl, extincting one of the lake’s endemic fish, the Utah Lake sculpin. These errors have one thing in common: instead of carefully observing and learning from the lake, we assumed we could remake it in our own image. This is a story that has repeated itself thousands of times around the world. Wendell Berry calls this “arrogant ignorance.”

Me describing what a sailboat looks like and how it works.

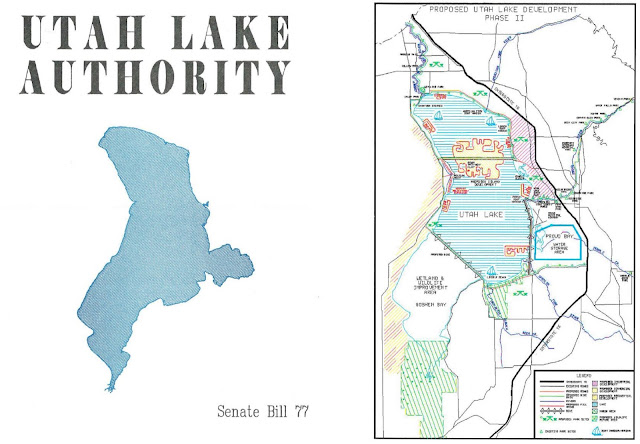

This isn’t the first time islands and dikes have been pointed at Utah Lake. This bill from 1989 wanted to “fix” the lake by destroying it similar to the current proposals under consideration.

For the past 40 years, we have taken a different path. We chose to invest in healing and ecological restoration. Rather than trying to transform the lake into something new, we decided to study and learn from the lake and begin undoing some of the mistakes we had made. Utah Lake had a huge advantage over other waterbodies such as the Great Salt Lake, which had suffered permanent modifications. Though not healthy at that time, Utah Lake was at least whole and intact. Starting with investments in wastewater treatment, we began to reduce the flows of excess nutrients and other pollutants to the lake. The listing of the June sucker as endangered accelerated these efforts, bringing diverse community partners to the table to discuss how we could restore the lake while still meeting our needs. We began removing the introduced species and testing methods for reestablishing native plants and fish. Collaborative agreements between farmers, cities, and other water users began restoring river flow to the lake—its lifeblood.Hashtag for real don’t pave the lake.

These efforts are now bearing fruit as algal blooms decline, native species recover, and people across our valley rediscover the beauty, power, and wonder of this unique ecosystem. Right at this delicate and crucial moment of healing and recovery, we need to have an extra measure of caution and commitment. Utah Lake’s recovery depends on sustained support, rigorous research, and robust public participation.

An osprey returns to its nest on the lake.

James Flaming Eagle Mooney and entourage performed a smudge ceremony.

So, I want us all to take a deep breath and ask ourselves, how did we get here? What are we considering and why? What are the policies and programs that have brought us to the brink of such a bad decision? Take a look at the signs around us. They say, “Don’t pave Utah Lake.” Are we seriously considering throwing away decades of restoration? Are we seriously considering destroying one of our state’s natural wonders for short-term profit? If we allow this project to move forward, are we going to need signs next that say, “Don’t bulldoze Mount Timpanogos”? “Don’t sell Bridal Veil Falls?” How many times do we need to learn this lesson? I believe we are better than this.

Bremen and Logan hold back the wind (and hopefully the islands).

You’re brilliant Ben, and we stand with you.

ReplyDeleteWell said, Ben. Utah, and Utah Lake, are lucky to have you. Wishing you well from afar...

ReplyDeleteThanks Ben...and thanks to Susan who has brought her friends, who might otherwise have been naive to what is actually going on, into the loop on this.

ReplyDelete