There are two ways to solve a water shortage: decrease consumption or increase supply. A century of trial and error in water security indicates that we should always start with the former option. The global water expert Dr. Rhett Larson recommends the following, prioritized approach:

1. Study the water system

2. Maximize conservation

3. After exhausting steps 1 and 2, augment flow as little as necessary

There are literally hundreds of reasons to follow this sequence, but here are three: conserving water is faster, more cost effective, and much more resilient to future changes than trying to increase supply. Compare this with augmenting water supply, which takes decades, almost always goes over budget, and is often obsolete before coming online (think about how well the Lake Powell Pipeline has aged).

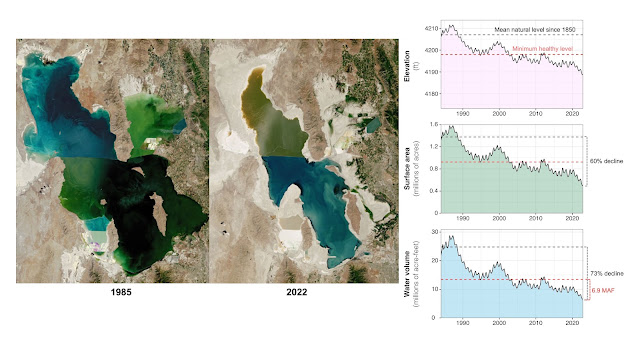

For decades, researchers and managers throughout Utah have been calling for more conservative water management. They have been warning us that we have been living beyond our means—using more water than is sustainably available. Great Salt Lake has been our line of credit, and we have been firmly in the red since my parents moved our family back to Utah in 1987. Years of kicking the conservation can down the road have put us in a situation where we need to rapidly reduce our water consumption by 30-50%. Otherwise, our debts will come due, and we will suffer the consequences of losing Great Salt Lake (see our recent report for an overview of that grim scenario).

Thankfully, we have a veritable cornucopia of common-sense conservation options at our fingertips. We can reduce agricultural water waste through new irrigation techniques and crops, update water laws to encourage conservation, and reduce the area of turf grass—currently the largest irrigated crop in the U.S. As one of states with the highest per-capita water use (~300 gallons per person per day), we have a lot of room for improvement.

But why reduce waste if we could just change nature instead? That is what a recent water augmentation pitch seems to propose. A Salt Lake County councilmember is suggesting that we wouldn’t need to reduce water use at all if we just made some changes to forest management. According to this councilmember, burning and logging the forests in the Great Salt Lake watershed could increase streamflow by 1.5 million acre-feet a year. Don't get distracted by overuse of water by agricultural and urban areas, the real problem is trees.

We addressed several counterproductive “solutions” in our recent rescue report. We recommended against building more dams, sacrificing the north half of the lake, ramping up cloud seeding, or artificially reducing evaporation of natural lakes. Unfortunately, most of these nonsolutions are still being actively considered or pursued. We didn’t address the “trees are the problem” proposal, and so I’ll do that now. If you want the in-depth treatment, check out Dr. Sara Goeking’s dissertation, which includes a meta-analysis of 78 studies, including 159 watersheds. If you prefer the op-ed format, here is a short article by Brian Moench. Read on if you want something in between 😊.

Here is a summary of Dr. Goeking’s work:

1. The prediction that streamflow would increase with reduced forest cover seems intuitive and is sometimes true. Paired watershed studies from the eastern US have shown that in humid watersheds with dense forest cover, streamflow often goes up following logging, wildfire, or herbicide treatment.

2. However, flow increases following thinning are neither guaranteed nor permanent without perpetual intervention. This is especially true in arid and semiarid watersheds (like the basins of Great Salt Lake), where loss of trees causes increased soil evaporation from loss of canopy shade and rapid shrub regrowth.

3. In regions like ours, forest thinning could reduce streamflow, as has happened in forests affected by recent pine beetle epidemics. Water will evaporate from soil, with or without trees present, and in warm and dry environments, the hydrologic value of trees as shade often offsets the amount of water that they transpire.

4. Even in humid watersheds where this technique sometimes works, tree thinning is rarely used to increase streamflow. This is because decreased forest cover often triggers major water pollution from erosion, ecosystem nutrient loss, and habitat degradation. Additionally, the flow response is extremely unpredictable and can cause flood damage.

5. There are viable reasons to thin forests, such as to reduce risk of severe fire, maintain habitat quality, and increase forest resilience to climate change. Natural or prescribed wildfire is the best way to achieve these goals.

There is another reason to question this proposal that only comes into play when you think outside the watershed. The idea that trees “use” water has been widespread in forestry for over a century. In some ways, this is perfectly reasonable when thinking about a single tree, but it is fundamentally incomplete when thinking about a region. For an inland area like Utah, trees are not a net loss of water, they are the proximal source. Most of the water that reaches the Great Salt Lake watershed only makes it this far thanks to upwind vegetation. Multiple hydrological research and management teams including ours have called for a paradigm shift.

Vegetation is crucial to “continental moisture recycling”. If you chop yours down in a misguided attempt to temporarily increase streamflow, you could reduce precipitation downwind. Human alteration of forests and grasslands has already weakened India’s rainfall, changed wind direction in the Amazon, and modified the extent of the Sahara.

Trees do not “use water”, they structure the global hydrological cycle and ensure watershed health. Everything from groundwater recharge to prevention of catastrophic flooding and drought depends on trees. Preserving natural vegetation will become even more important to maintaining secure food and water supplies in our time of rapid environmental change.

Ultimately, forest thinning to increase streamflow is very similar to cloud seeding. They both are unproven techniques that are unlikely to yield sustainable increases in water yield. But even if they were successful, they would simply be scavenging moisture from downwind, nullifying their effect at the scale of a watershed as large as Great Salt Lake’s.

Call me conservative, but given the stakes of losing the lake, I think we should use an approach that is proven and much more affordable: use less water.

.jpg)