Too many people on the bus from the airport

Too many holes in the crust of the earth

The planet groans

Every time it registers another birth

Paul Simon

Nobody goes there anymore, it's too crowded.

Yogi Berra

Back in the innocent days before the pandemic and the lawsuit, my college interviewed me about what individual people could do to live more sustainably. I told them my three recommendations, and they made this cute video a few months later:While none of us can solve air pollution and climate change on our own, it is empowering to know that we can substantially reduce our personal contribution to these problems by making thoughtful changes in our transportation, diet, and public participation. Additionally, these individual choices contribute to systemic change through personal example, economic pressure, and the political process. I have seen this play out on issues ranging from protecting Utah Lake to accelerating the local transition to renewable energy.

A couple weeks later, I heard from a colleague who had seen the video. He said that he appreciated the thought but wondered why I didn't recommend the most effective way of reducing your environmental footprint: having fewer children. He cited what has become a highly-cited paper in sustainability circles, entitled: The climate mitigation gap: education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions by Wynes and Nicholas 2017.

The paper has some valuable insights, including the titular conclusion that the effectiveness of various climate-smart choices is usually not reported in textbooks. I see this all the time in the real world (check out this pretty but useless animated infographic by Columbia University). Many people do not know what changes could effectively help us create a sustainable future, and most people do not know how to prioritize potential changes. For example, implementing a single meatless day a week has almost no effect on environmental footprint, while switching to a plant-rich diet reduces agricultural emissions and use of water, land, and nutrients by approximately 90%.

This cutting-edge paper by Kim et al. compares the greenhouse gas footprint of different diets for almost all countries (click for higher resolution version). In the U.S., you can reduce your dietary greenhouse gas footprint from around 2 tons to 200 kg of CO2 by switching to a plant-based diet. That means we could feed nine people with the resources we currently use to feed one.

But as Mark Twain might have said, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” Wynes and Nicholas conclude definitively that the most effective personal action is having fewer children. They rank this choice as 30-times more effective than the next recommendation of living car-free (60 versus 2 tons of CO2 saved). This conclusion was the perfect material for a whole constellation of smug infographics (good coverage by Vox here).

I teach all my students that the most important time to exercise their critical thinking is when they are confronted with information they agree with. It is so easy to welcome confirmatory evidence while dismissing data that doesn't match our prior beliefs. It is comforting and validating to collect numbers and arguments that we want to believe. However, if we are committed to learning, we should cultivate a taste for having our beliefs challenged. Whether or not Wynes and Nicholas' argument appeals to you, let's give their reasoning a real look.

One disclaimer before we dive in. Arguments about overpopulation have a long and troubled history that I can't unpack in a single blog post. Giorgos Kallis has a good book on the topic that is reviewed by the Inquisitive Biologist here. Rather than wrestle with the xenophobic and elitist worldviews of many population control advocates, I'm going to take Wynes and Nicholas' argument in good faith. Let's simply ask the question, is having one fewer child the most effective choice we can make to protect the environment?

Here is a figure of global fertility rate, expressed in the lifetime number of children per woman:

Notice that almost all industrialized countries are at or below replacement. This means that more than 80% of global greenhouse gas emissions are occurring in countries that are at or below replacement.

The global environmental footprint of humanity is the product of the number of people and the average per-person consumption. When we are talking about total amount, it's the mean that matters, not the median. For those of you who have taken math recently, you may remember that the mean is highly sensitive to extreme values. One very high number can outweigh thousands or millions of low numbers.

The pattern of global consumption is a lesson in extremes. The wealthiest 2,200 people have more money than the 4.8 billion poorest. Look at this intra- and international analysis of per-capita carbon emissions compiled by the Carbon Brief:

Beyond the first-principles analysis of variation in fertility rate and consumption, there is a fundamental flaw in Wynes and Nicholas' method of calculating future emissions. To estimate the savings of having one fewer child, they use a method proposed by Murtaugh and Schlax in 2009. They apply a projected consumption curve that assumes stable or increasing per-capita consumption through 2100. They then divide the summed emissions between the parents and call it a day.

There are at least two problems with this method. First, it doesn't reflect the actual trend of decreasing per-capita emissions. New technologies, increasing efficiency, and cultural changes have thankfully allowed us to now produce much more wealth per unit of CO2 than we did in the past. Indeed, normalized emissions have dropped by 50% since 1990, and the rate of decline is rapidly accelerating thanks to the renewable revolution. Second, if we accept their assumption that per-capita consumption is going to dramatically increase, we are toast no matter how few children we have. If everyone currently on the planet lived an American lifestyle, we would need 5.1 Earths to support the current 7.8 billion people. We can easily outstrip the capacity of the planet without adding any more mouths.

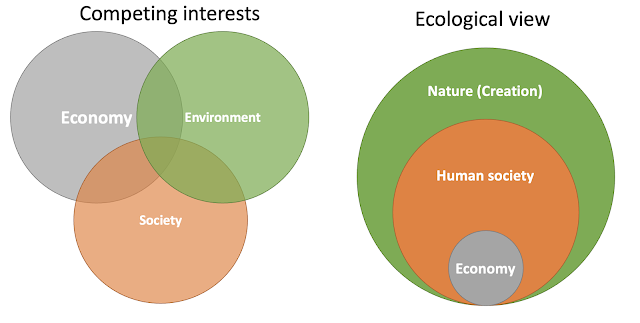

For moral and practical reasons, our focus should be rapidly decreasing per-capita consumption. We see this conclusion in thoughtful secular and religious teachings. Barry Commoner wrote in 1973,

When any environmental issue is pursued to its origins, it reveals an inescapable truth – that the root cause of the crisis is not to be found in how men interact with nature, but in how they interact with each other – that, to solve the environmental crisis we must solve the problems of poverty, racial injustice and war.

The scriptures of the restoration laid out the same truth more than a century prior:

For it is expedient that I, the Lord, should make every man accountable, as a steward over earthly blessings, which I have made and prepared for my creatures. I, the Lord, stretched out the heavens, and built the earth, my very handiwork; and all things therein are mine. And it is my purpose to provide for my saints, for all things are mine.

But it must needs be done in mine own away; and behold this is the way that I, the Lord, have decreed to provide for my saints, that the poor shall be exalted, in that the rich are made low.

For the earth is full, and there is enough and to spare; yea, I prepared all things, and have given unto the children of men to be agents unto themselves. Therefore, if any man shall take of the abundance which I have made, and impart not his portion, according to the law of my gospel, unto the poor and the needy, he shall, with the wicked, lift up his eyes in hell, being in torment.

Are there limits to how many people the Earth can support? Of course. Are the current ecological threats to our civilization primarily caused by overpopulation? No. If we live within our means and sustain those who sustain us, the Earth will be perfected, and there will be enough and to spare for all human and nonhuman peoples.

Here is my response to my colleague about the paper:

Thanks for reaching out and happy thanksgiving. I saw this paper when it came out, but didn’t read it in detail until now. It’s an important study and a crucial question. Their point about most textbooks not focusing on what matters most is really important. However, I do have a few issues with their first recommendation and specifically with their method of assessing the CO2 footprint of having a child.

First, they apply average historical consumption rates to the child. The intra and international variation in per capita consumption ranges two orders of magnitude. If a family implements all (or even some) of the best available practices, the footprint of their child would be much smaller, and therefore the decrease of not having a child much less. More importantly, in my opinion, the influence of having a child in such an environmentally engaged and concerned family could accelerate the transition to clean energy that we desperately need. If that doesn’t happen quickly, then increasing consumption will push us past any climate targets even if no one else is ever born.

Second, the analysis thankfully is applied to developed countries, rather than across socioeconomic stages. Overpopulation has long been blamed for many environmental crises, though the argument is usually reserved for low and middle income countries, which have a fraction of the consumption of upper income countries. However, in the case of this study, the authors neglect the issue of immigration. They assume that if one less child is born in a developed country, then there will be one fewer consumer in that country. Recent trends in immigration show that isn’t the case (sustained immigration to developed countries has offset some or all of decreases in fertility).

Third, population growth has shown to basically scale negatively with socioeconomic development, dropping to replacement or below in the most developed countries. What scales in the wrong direction is consumption. Looking through time or across socioeconomic levels, the fewer children a family tends to have, the more that family tends to consume.

Together, this leads me to the conclusion that focusing on decreasing consumption and catalyzing the transition to renewable energy and sustainable lifestyles are much more important than trying to limit fertility. We have the technology and financing to implement a rapid decarbonization of our economy over the next 20 years (do you know Project Drawdown and Rewiring America?). My conclusion is that we need all hands on deck to make sure this happens rapidly and equitably. On a PR level, population control measures are a nonstarter for many conservatives. On a practical level, I don’t think they could ever be effective given rates of increase in consumption.

I talk about the population versus consumption focus some in this Kennedy Center lecture.